Turtle People

A red-eyed dune buggy, its headlights dimmed with patches of cellophane, cruises the southern beach of Wassaw Island, off the Georgia coast, at midnight. Otherwise, the beach is deserted, lit only by stars and a new moon. Suddenly the buggy stops. David Veljacic, a Caretta Research Project intern, and several volunteers jump out and run up the beach, following the distinctive path left by a nesting female loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta).

Just as they locate the nest, volunteer Monique Dailey spots the retreating loggerhead as it heads back into the surf. Veljacic’s team shifts gears swiftly and runs toward the ocean. Veljacic looks for a tag, but this turtle doesn’t have one yet. With the assistance of a volunteer from inner-city Washington, D.C., Veljacic hooks a metal tag into the turtle’s right front flipper, which will help biologists study the population.

Tagging loggerheads and patrolling Wassaw’s beaches during nesting season are just part of what the Georgia-based Caretta Research Project does. The 30-year-old group, working in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Savannah Science Museum and the Wassaw Island Trust, aims to learn more about the elusive loggerhead, which spends most of its life in the sea, and to protect its declining population. The project uses volunteer teams to tag female loggerheads, locate their nests, relocate them if they are too close to the tide line and protect the nests from predators with wire mesh.

Relocating a nest is tricky work. Volunteers have to dig out the eggs by hand, sifting the sand gently, one handful at a time. Volunteer David Howard explains that he must not put insect repellent on his hands before handling turtle eggs. The toxins in the repellent can penetrate the egg’s shell and kill the turtle, he says. In the late summer, after the nest is 45 days old, the wire coverings are removed. The turtles hatch and churn around in the nest for up to three days, drying out and straightening out their stomachs. Then, says assistant project director Mike Frick, they leave the nest and toddle on down to the ocean where they will spend the rest of their lives.

There’s plenty of evidence to suggest that the project has been successful in curbing the steep decline in loggerhead numbers. When he joined the project in 1986, Frick was seeing 50 to 60 nests on Wassaw per year. Now, in a good year, he sees more than 100. But, with the usual caution of scientists, Frick says you can’t assume the Caretta project is helping loggerheads survive. Development on nearby islands may be driving nesting turtles to Wassaw, he says. Project director Kris Carroll says it’s still too soon to evaluate Caretta’s success.

The Volunteers from Petworth

“This project is legendary on our block in Washington, D.C.,” says Caretta project volunteer Julie McCall. McCall, a lifelong conservation volunteer and labor organizer, read about the Caretta Project seven years ago in the book Volunteer Vacations. She had planned to volunteer at several projects, but “I never got past this one,” she laughs.

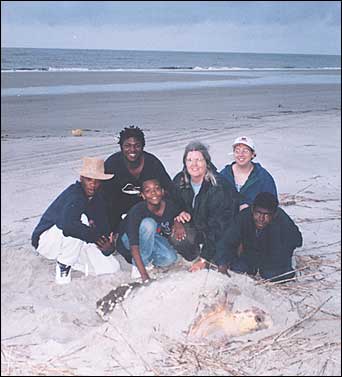

In her second year, McCall brought several high school students from her inner-city neighborhood along. “Everybody thought I had lost my mind,” she says. “But you have to take a few risks.” The experiment was an immediate success. “They loved it,” McCall reports. “They jumped right in.” Now she brings a team of young people from Petworth, her D.C. neighborhood, for one week every summer. Participation in the Caretta project costs about $550 per person, so McCall devotes quite a bit of energy throughout the year to raising money for scholarships for the four or five students who will make the trip.

The volunteers patrol the beaches from nightfall to dawn in open vehicles called “mules.” For a week, the young people from D.C. keep a sharp eye out for turtles and for their distinctive “crawl,” which is the trail left in the sand by the nesting female’s flippers. Even after each long hard night of turtle patrol, the Petworth team is full of energy at dawn. At 7 a.m. one morning, volunteer Lawrence Baltimore announced that he wanted to go bird watching.

The loggerhead sea turtle is still largely a mystery. Scientists don’t know how long they are capable of breeding, though Frick suspects many of the turtles he sees on Wassaw are older than the volunteers. Even less is known about the evasive male loggerhead, who never reappears on the shore. But one thing we do know is that they like to come home to breed, and that they can get by with a little help from their friends.