The Burning West

After a Series of Tragic Fires, Loggers Go on the Offensive

Wildfires ravaging the American West have citizens, civic leaders and environmentalists searching for answers. Many blame our country’s past attitude towards fire, and a U.S. Forest Service (symbolized by the venerable Smoky Bear) that has been suppressing healthy, natural burning for too long. Fuel supplies—leaves, underbrush and other tinder—usually consumed in small blazes have instead been accumulating for up to 70 years, and when a spark finally catches the forest erupts into a destructive inferno.

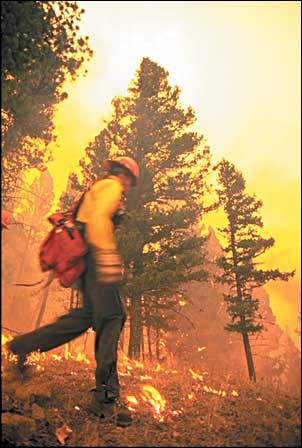

Western firefighters worked overtime last summer. Meanwhile, the debate over fire suppression continues.

Karen Wattenbaker Photography

For many Republican leaders the answer is simple: Remove the fuel by selectively cutting down trees and clearing underbrush in densely wooded areas. "Through site-specific thinning of small trees and underbrush

scientists are reducing the likelihood of forest fires, and reducing their intensity if fires happen to start," says Senator Jon Kyl (R-AZ). In his proposed 2003 budget, President Bush is pushing for the creation of "charter forests" outside the Forest Service’s control. These woods would be managed locally for the purposes of "emphasizing local involvement and focusing upon more forest ecological restoration or hazardous fuels reductions."

But some environmentalists fear that these politicians are generating sympathy for the timber industry in the name of fire suppression. President Bush disappointed the Alaska Rainforest Campaign in May when his administration pursued a court-ordered wilderness review of the nine-million-acre Tongass Forest in Alaska and concluded that none of it was to be protected. A number of industrial timber sales are now planned for formerly roadless areas. "The Bush Administration had a clear-cut choice and it sided with the timber industry," says Michael Finkelstein of the Alaska Rainforest Campaign. "Meanwhile, the overwhelming public support for protecting the last remaining Tongass roadless areas has been tossed out the window."

Designed to protect 58.5 million acres of national wilderness from logging and road construction, the Roadless Area Conservation Rule was adopted by Congress last year. According to the Wilderness Society, "More than 2.3 million comments have been received by the Forest Service with upwards of 95 percent of them in favor of the strongest protections possible." However, the rule has yet to be executed and Bush intends industry-friendly amendments. As it stands the Roadless Area Conservation Rule allows for logging and road construction when certain practicalities demand them, including the fighting and discouraging of forest fire.

Fear of conflagration has been used to protect the timber industry in the past. Senator Mike Enzi (R-WY) invoked fire anxiety in 2000 to help defeat a proposed amendment to the Interior Department Appropriations bill that would have ended the selling of timber by the U.S. Forest Service. Catastrophic fires will continue, he says, "until our forest managers are allowed to thin out the forests and remove the dense undergrowth and some of the increasingly taller layers of trees that create the deadly fuel ladders that feed these fires." Whatever the science, Enzi made clear his priority remains defending forest product jobs.

As if it weren’t hot enough already, some politicians are turning up the heat by blaming environmentalists for problem blazes. In a recent Denver Post, Senator Ben Campbell (R—CO) editorialized that "environmental groups" were preventing authorities from effectively fighting fires. "Although these groups claim to want the best for our forests," he wrote, "they argue against sound forest-management policies

Their frivolous lawsuits fan the fires." Kyl agrees, targeting "groups on the radical fringe" that oppose any efforts to thin forests.

The Sierra Club claims these accusations are an inaccurate distortion. "The Forest Service has not been hampered from preventing fires by thousands of lawsuits. Congress" own General Accounting Office found that of 1,671 "fuel reduction" projects last year, only one percent were appealed, and none were brought to court," the club said last summer.

Mudslinging aside, evidence suggests that thinning forests can in some situations lead to more manageable combustion. "We have empirical evidence that thinning lessens the severity of fires," says Mike Da Luz, a National Fire Plan coordinator with the Forest Service. "On several large fires in Colorado, the intensity and speed were favorably influenced in forests that were treated with thinning."

Scott Stephens, professor of fire science in the College of Natural Resources at UC Berkeley, says, "Harvesting can make forest sustainability better, but the devil is in the details." Improper thinning, he says, can lead to conditions that make destruction worse. "If you thin in a place with a high canopy cover and slim trees," he says, "you increase the wind speed inside the forest, the amount of sunlight hitting the ground and dryness of the forest floor. That coupled with poor fuels management can lead to worse fires. But if you do things properly, those increases in winds and dryness aren’t necessarily a problem and may actually be more natural."

In the New York Times last June, Stephen Pyne, an Arizona State biology professor, argued that thinning techniques should be used selectively. The Sierra Club agrees, advising homeowners to protect their property by "clearing flammable materials within 30 to 60 feet of your home." But the club believes prescribed burning better serves the health of the forest. "Restoring the natural role of fire to a landscape often provides the best wildfire prevention and pays off with long-term financial savings," the club says.

"What many areas need is a kind of woody weeding," Pyne writes, "which removes woody vegetation that has replaced natural grasses—but not logging, because the debris or slash left from clear-cutting is among the most hazardous fuels imaginable."

But in extreme conditions, there’s nothing homeowners can do. "I can’t say things like "fire-proofing,"" says Da Luz. "This is a natural disaster, like a hurricane. What could you do to hold a hurricane back?" Because of fire threats, owning property in woody environments is financially risky. "Most people pick the mountains because of the aesthetics. But their property values will change if that area goes through a fire."

Da Luz says the Forest Service intends to combine forest thinning with prescribed burning. However, he doesn’t project a rapid return to healthy conditions, suggesting that thinning is likely to continue indefinitely. "When you’re talking 100 million acres, it’s not like you could fix it in 70 years," he says.